by Caitlyn Pray, Student Reporter

Who won? Melissa Maharry wasn’t sure.

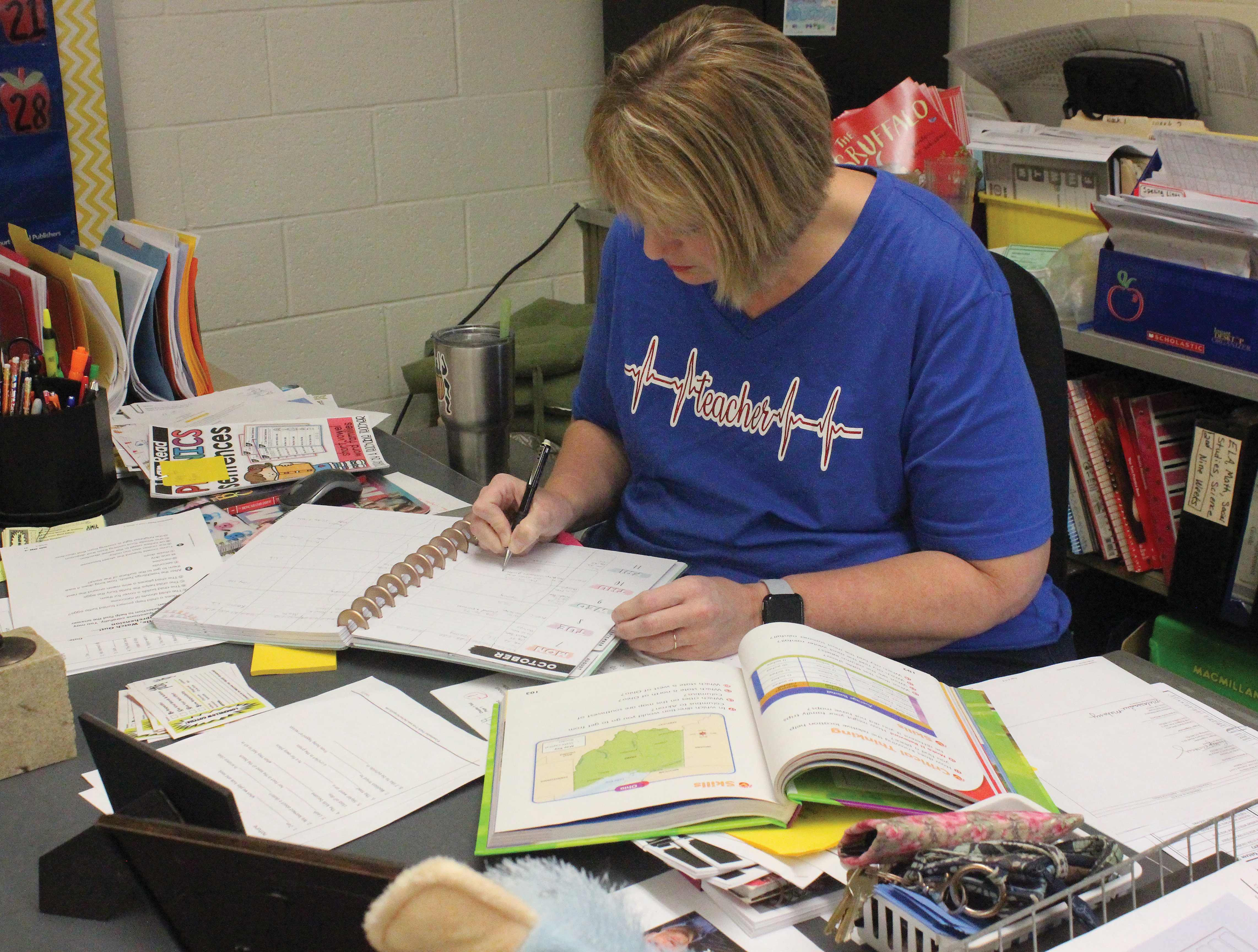

Locking her classroom door where the day’s outbursts, tantrums and headaches had occurred, Maharry left her job for the day wondering if she had set the standard for her classroom or if the elementary students had victored. It was just another day of work.

Like many teachers, Maharry encountered a different world of scenarios in her classrooms than what she may have expected while earning her degree in education.

“Hands on experience definitely taught me more,” Maharry said. “I taught children that had emotional problems and so there were fist fights, cuss words that I had never heard in my life and so in that aspect I was not prepared for any of that.”

When it comes to education about education, Maharry has experience. Graduating with two degrees from Hastings College in Nebraska, one in education and the other in special education, Maharry has served in the public school system for the past 19 years and Longfellow Elementary School in Alva for 15 of those years.

With so much experience in the field of education, Maharry says she has seen both what aspects of her degree have been applied and have helped prepare her for her career and which have not.

“I think my special education training maybe prepared me a little more than elementary did,” Maharry said. “Just because the teachers would do role playing in there so you’d have to pretend that you were like the parent and pretend you were talking to the student and trying to help the student. I think looking back that that helped me more than the elementary part did. In elementary education we had to make lots and lots and lots of games that I have never ever used.”

Chris Eckhardt, Alva High School English teacher for nine years and counting, said that although he was alternatively certified, he also wasn’t entirely knowing of what he was getting into when he stepped into his classroom for the first time.

“Honestly, I thought I was a lot more prepared than I was,” Eckhardt said. “You come in and after taking all these courses you think you know all of these things, but in a static environment—a classroom environment—you learn all things of ‘this might happen, this might happen,’ but when you get here it’s a completely different deal. I think I was prepared in terms of the material I wanted to teach, but I think I was less prepared for the sum-up of the way the students behaved maybe. Some of the issues or concerns that they might have with learning were not something that I was expecting to have in some of those cases.”

Knowing this, Christee Jenlink, associate dean of education at Northwestern Oklahoma State University, says that experience is something they try to equip their student teachers with early for success.

“Placing our students out in schools as much as possible is a standard for us because no amount of teaching in a classroom is going to be anything like out in a classroom,” Jenlink said. “I think that’s one thing our program does very well is that it gets our students out in schools as much as possible. You can go through all the scenarios and ask ‘What would you do?’ but there’s nothing like having 24 4-year-olds in a room or 17 juniors in a classroom. Nothing can totally prepare you for that other than being there.”

However, while this report of feeling unprepared is a common one among public schools, many teachers in the Alva community also believe they were prepared for the chaotic world in the classroom before them.

“Teaching is very challenging; it is new every day, yet I don’t

think it’s more challenging than I thought it’d be,” Macey Alexander, Northwestern alumna and first-year middle school teacher in Guthrie, said. “I felt prepared in knowing what lied ahead during my time at Northwestern.”

Halah Simon, Alva High School English teacher of 17 years, said although she has learned a lot over the years the experience has been a glorious one for her.“I would say teaching has been nothing but good for me,” Simon said. “I love coming to work every single day; I love my kids. Every year I think, ‘Oh I don’t want this batch—especially when they’re predominantly seniors—to leave and go,’ but then the next year a new group comes in and I love them just as much, so that’s been really rewarding to me to invest in the relationships with my kids and be able to see them go into their future and be in the world and really shine.”

Simon said that teaching has not only been beneficial to her students, but has shaped her in ways throughout the years as well.

“Teaching has taught me a lot of patience,” Simon said. “It has taught me how to multitask and really how to do a lot of different things at one time. I think teaching has made me a better person; it has made me see people for who they are, appreciate them more and be able to see what each person can bring to the table.”

As Maharry said, there are positive and negatives to both sides, however. While enthusiasm, passion and love drive teachers to press on, challenges are always on the horizon and usually in the face of many educators today. To combat this, colleges and universities across the state and nation put standards in place to prepare students for the real-life classroom the best they can. Northwestern Oklahoma State University is one such institution.

“We have as many bodies as we have standards that we have to maintain for our program to be accredited,” Jenlink said. “Within those standards we try to thoroughly prepare the individuals in content—what they’re going to teach—and also delivery—how they’re going to teach it. Our philosophy is that we need to prepare people to work with young people out in schools. Our first priority is the young people out in schools so we always keep those young people in mind as we prepare our individuals to go out and provide an education to those young people.” Certain public schools have also offered incentives to their teachers to try to keep them on.

“The last three years they [The Alva School Board] have approved stipends for us,” Maharry said. “We have to complete our training on bloodworm pathogens and autism and there are like ten videos of topics like those we have to watch, and when we do we get the stipend. It’s nice; it helps pays for Christmas presents since we get our stipends in December.”

Eckhardt also explained that at the high school incentives are given in the form of a wide array of options for classes for the teachers to choose to teach, as well as fixed bonuses in pay over the next several years. Community plays an important role in the incentives as well.

“Alva is a good place to teach because the community is supportive and the parents are there; f I had to teach somewhere else I very well might not be there,” Maharry said.