By Cade Kennedy, Sports Editor

As the third and fourth grade students at Freedom Public School walk into the classroom, they’re greeted by a familiar face, but she’s technically their new teacher.

These students continue to rotate from classroom to classroom as they watch teachers, librarians and other staff pass the title of third and fourth grade teacher back-and-forth.

Because of a teacher shortage impacting Oklahoma, scenes like this are becoming more frequent across the state. It isn’t just happening in public schools, but across college campuses as well.

This shortage isn’t a new problem in Oklahoma. Teachers have been fleeing the state or retiring early for the past decade. In July, the Oklahoma State Department of Education issued 1,473 emergency teaching certifications, an all-time high for a single month, according to the agency. Despite the record high, those certifications only made up 41% of the 3,593 emergency certifications issued this summer.

Despite the certifications, the Oklahoma State School Boards Association’s annual back-to-school survey found 1,019 teaching jobs remain open in 328 school districts that serve 77% of Oklahoma’s student population. In the nine years the survey has been conducted, those 1,019 jobs set the record for the most openings in a year.

“Education leaders are incredibly grateful for the work legislators have accomplished in recent years in an attempt to ease the shortage and strengthen the teacher pipeline,” OSSBA Executive Director Shawn Hime said. “But the survey and other data paint a pretty clear picture: The work is far from done.”

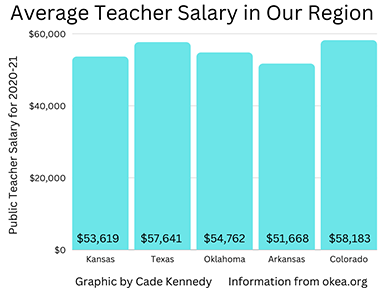

One of the main reasons behind the shortage is money. Oklahoma is ranked 34th out of all 50 states in teacher pay, with the average Oklahoma teacher earning $54,762 for the 2020-2021 school year, according to the National Education Association. This figure puts Oklahoma teachers slightly above the regional average of $54,622 but below the national average of $65,293.

Oklahoma ranks 45th when it comes to per-pupil spending, as the NEA reported that only $10,553 is spent per student in Oklahoma. The national average is $14,360.

“It’s shocking to see these numbers in print, but they really help inform us of why we have a teacher shortage and why our schools have a hard time finding bus drivers, custodians and other support staff,” said Katherine Bishop, president of the Oklahoma Education Association, the largest teacher’s union in the state.

While the shortage has persisted, several attempts to fix it have come and gone. One of the more memorable attempts occurred in April 2018, when teachers went on strike statewide to protest low wages, among other issues. The strike ended after 10 days, when the state Legislature voted to give teachers a $6,100 raise.

Another raise could soon be in store for the teachers of Oklahoma. The Oklahoma State Board of Education passed a $5,000 pay raise proposal Sept. 22 to raise the minimum starting salary for teachers to $40,000 and average teacher pay to $59,000 annually.

If the raise can make its way through the Legislature, the only state in the region with a higher salary would be New Mexico. Teachers there will earn $64,000 because of a $10,000 salary increase.

REACHING

THE CLASSROOM

Despite the potential solutions, the effects the shortage has had on students and teachers is still being felt across the state.

One of the schools dealing with the shortage is Freedom, a school in western Woods County in northwest Oklahoma. The district is small enough that the graduating class rarely numbers above five. Inside the school, rooms for the robotics team and esports team are present, but there is no third and fourth grade teacher.

Freedom, like many other schools in Oklahoma, had trouble finding teachers during the summer. Unlike other schools, Freedom did not get a single applicant for the position.

“We were all stunned,” Freedom principal Michelle Shelite said. “We kept asking each other, because we had put it out that they could contact three different people, and none of us were getting anything. So, we came together and said, ‘We aren’t getting anything. What are we going to do?’ So, we started brainstorming, and I got teachers that were certified in other areas to jump down and take care of those classes.”

Teachers at Freedom have bundled students in various grades together for the past decade, but with the teacher shortage continuing, other district employees are having to pitch in to teach. Despite the constant movement from teacher to teacher, Shelite said the staff has handled the transition well.

“They have done an awesome job,” she said. “I am very proud of my staff. I could not be doing what I’m doing this year without them. Everybody looks at it and goes, ‘Well, you only have two or three students,’ but they still have to do all the same work doing two or three grade levels within the same classroom, which makes it even harder.”

One of the teachers at Freedom dealing with this adjustment is the first and second grade teacher, Cindy Wilson, who has taught for more than 30 years. After all those years, she said she never thought she would be teaching three grades at once.

“You always have so many levels in what children are capable of doing, whether it be socially and academically in just one class, and here we have three, but we always seem to make it work,” Wilson said.

Freedom isn’t the only school in Woods County facing the situation. Alva Public Schools, the largest district in the area, has had difficulty hiring teachers as well. In his five years at Alva, Superintendent Tim Argo said he has seen some changes in the number of applications.

“Initially, there was always a large applicant pool of teachers, and we have seen over the course of the last couple of years that pool has shrunk,” Argo said. “It was probably especially felt the hardest this year. As with hiring teachers this year, we really struggled. We were able to fill most of our positions, but we had two that we were unable to fill, so we had to cut some classes.”

While cutting classes is the short-term solution for Alva, Argo said the district has a plan to try to prevent this situation from happening again.

The school district is working with Northwestern Oklahoma State University to create a so-called “grow-your-own” program that identifies school support staff and high school students interested in teaching.

Once educators identify potential future educators, they can work to get them in college to study education and return to teach in their hometown.

“We want to capture those students and encourage them to get into education so that we can have a foot in the door earlier with applicants,” Argo said.

While local schools hope the program will help both Northwestern and school districts, the 17 student teachers at Northwestern this semester hope they can find the job that’s right for them.

“Right now, there’s a lot of excitement about the job possibilities they have,” said Dr. Jennifer Oswald, chair of Northwestern’s Division of Education. “Whenever I graduated, you would have 15 applicants for one job. You had to stand out, and to them [now], they’re having 15 job offers, so it’s exciting for them to get to go into schools and have interviews and basically choose the one that fits for them.”

UNIVERSITIES FACE

HIRING STRUGGLES

While Northwestern tries to help local communities with the teacher shortage, the university is dealing with its own shortage of professors.

“The shortage varies by department, as some departments are producing higher numbers of graduates from graduate school,” said Dr. James Bell, vice president for academic affairs.

Northwestern is not the only university struggling to find help. A recent poll from the Chronicle of Higher Education found that 64% of universities had more difficulty hiring educators this summer than they did during the rest of 2022.

“Northwest Oklahoma is a fantastic place to live, but not everybody knows that,” Bell said. “When people apply, they have some preconceived notions about what it would be like to live in a rural area. … We know that it’s great. They don’t know that yet.”