By Richmond Adams

Movie Reviewer

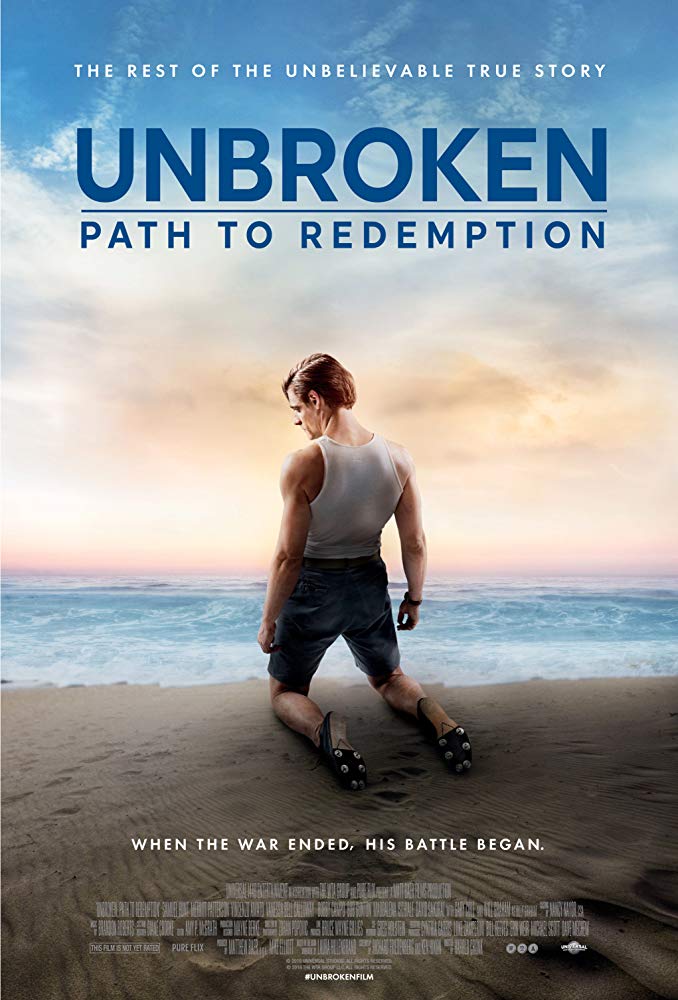

As we noted some time ago when reviewing “The Shack”, it is usually awkward territory in the realms of religion and politics, so one must tread with as much grace and courtesy as possible. Such reminders being given, “Unbroken: Path to Redemption” is not a film in the same way of a John Ford or Steven Spielberg production, and it is not meant to be. Distributed by Pure Flix

Entertainment, the same company that produced “God is Not Dead (I and II)”, the present title indicates with exacting honesty what viewers will witness for just beyond one and one-half hours. In itself, “Unbroken” tells the true-to-life homecoming of Louis Zamperini (Samuel Hunt), a World War II veteran who endured unspeakable horror as a prisoner of war in the Pacific theatre for over two years before his rescue at war’s end in 1945.

As he returns to Southern California, Mr. Zamperini begins to have parallel lives, one of which portrays a conventional middle-class American through reunions with home, family, and eventual marriage to Cynthia Applewhite (Merritt Patterson). Mr. Zamperini’s second life, however, soon descends into alcoholism as a means by which to escape his Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) caused by the torture he endured at the hands of a sadistic prison guard known as “The Bird” (David Sakurai).

The inevitable conflict between these parallel lives led to the near collapse of the Zamperini marriage and a deepening spiral of more alcoholic despair. Interspersed with these domestic sequences are scenes that reflect some of the abuse undergone by Zamperini which will horrify and sicken almost any viewer (not a peep was heard in the theatre when these episodes were shown). Fortunately, however, Mrs. Zamperini was a person of faith who began to attend revival services led by a young Billy Graham (Will Graham, an actual grandson), whose rise to international prominence actually began as a result of these events in the late 1940s.

After some convincing by Mrs. Zamperini, “Unbroken” reaches its fulfillment when Louis comes to a faith, in the language of evangelical Christianity, which restored his sense of self-worth as a child of God. Interestingly enough, the film shows this experience not as a reaction to the sermon, but as Mr. Zamperini was called back into the revival tent by Reverend Graham during a post-sermon prayer.

That very human effort by Reverend Graham to make a connection, no matter the specific language of faith that he uses to do so, is what gives the film a singular strength. Both for people of faith and those who find their path by other means, “Unbroken” parallels the ideas of the Holocaust survivor Dr. Viktor Frankl, who wrote that by somehow finding any sort of meaning, we humans are able to have what might be called a sense of place during the most unimaginable of circumstances. “Unbroken” may not be for all viewers and I would express caution for young children, but in how it presents, in the term of evangelical Christianity, a “message” through a realistic and human way, it is worth both a look and some thought.

Three and one-half stars from five.