by Megan Brown, Student Reporter

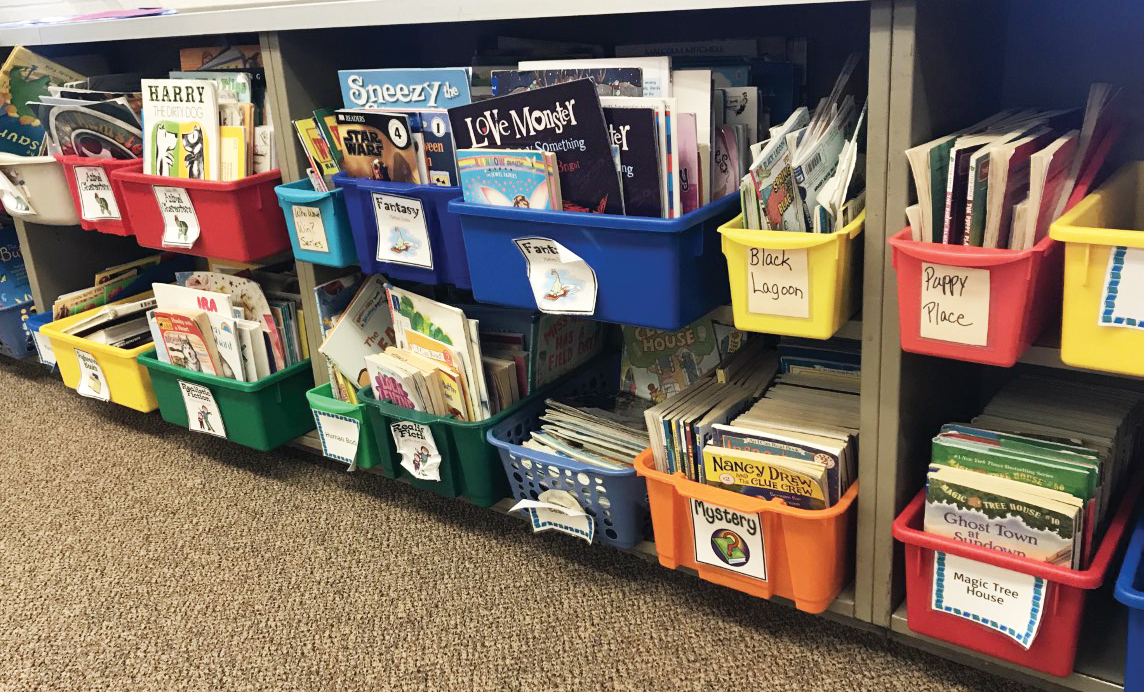

On the other side of a door in the fifth grade hall at Lincoln Elementary, you will find a colorful classroom filled with educational games and fun decorations.

Across Oklahoma there are many bright, fun-filled classrooms, but many of them were financed by the teacher whose name is posted outside the door.

Sara Eckhardt, who has taught fifth grade at Lincoln for around seven years, proudly said that the majority of her classroom was filled with her personal belongings.

“Most of this is mine! My mom was a teacher and she retired the year that I took this job,” Eckhardt said. “She shoved everything at me and said, ‘here take this.’ It was passed down to me.”

While Eckhardt has a room full of educational hand-me-downs, teachers across the state are faced with using their own funds and resources to create the environments they shape minds in.

Oklahoma’s public education has been the headline for multiple stories over the past few years, but are they covering everything they should be? Many educators believe they are missing a few key components.

While the stories continue to cover funding and the teacher shortage, other aspects have been left out.

Nick Lyon, an English teacher at Crescent High School, has been in an Oklahoma classroom for nine years and has found some holes in the coverage.

“I wish that there was more press just about the budget in general,” Lyon said, “basically how the budget works and how like some counties have more oil money.”

Crescent High School is located within Logan County and is one of many schools Lyon has taught in, and while he has found it to be the most supportive school system he has worked in so far, some challenges exist.

“Logan County, for instance, has zero oil drills or oil wells at all, so like all four of the schools in Logan County are really poor and struggling,” Lyon said. “If you go right across the county line to Kingfisher County, they have tons of money, just extra money and stuff because they get the same state budget that we get, but then on top of that, oil tax money coming in.”

The lack of funding has led to many struggles for the teachers and the classrooms, including school supplies shortages and educators turning to alternative sources of income.

Lyon touched on the fact that each student has a laptop to use but this can be used as an excuse to not purchase the textbooks. While he says the courses can be taught without books, it is often times easier to have the material at hand.

Yesenia Buckhaults, a math teacher at Alva High, said she is thankful that she was able to attend a conference where she and the other teachers received gift baskets of supplies. These materials have helped her greatly in her classroom.

School supplies shortages and budget issues have made the news consistently, but according to Oklahoma teachers, those outside of the classroom are missing the main point: teachers teach to teach, not for the money.

“I just really like helping the students learn new things and expand the way they see the world,” said Cecely Franz, a fourth grade teacher in the Alva Public School system. Melissa Maharry, who teaches second grade at Longfellow Elementary, referred to an article by Peter Greene in Forbes magazine. The article states that in fact, plenty of people want to teach, so it should not be referred to as a teacher shortage.

“You can’t solve a problem starting with the wrong diagnosis,” Greene said.

The article goes on to relate the situation with teacher pay to other scenarios.

“If I can’t buy a Porsche for $1.98, that doesn’t mean there’s an automobile shortage,” Greene said. “If I can’t get a fine dining meal for a buck, that doesn’t mean there’s a food shortage.”

While Maharry said the pay in Alva is good, she has found teacher pay in other areas of the state, and across the country, just isn’t cutting it.

“If I had to work at the bank and I was expected to do this and I might get hit or kicked by somebody and I might get yelled at or spit on, for X amount of dollars, how long would I put up with it?” Maharry said. “You wouldn’t, but yet teachers are expected to.”

America has long been known for the education systems, but it has become apparent that the educators need to see changes.

Buckhaults, who lived in Mexico until third grade, said she is passionate about free education but is fearful that America might have taken the concept too far. “Education is something that I’m really passionate about, and I think that’s why I take things personally,” Buckhaults said. “It’s frustrating for me to watch some kids kind of just fall down the cracks.”

She said after completing the first few years of her education in Mexico, she believes America has allowed the idea of free education to create children and parents who do not appreciate the opportunity.

“I was always taught that education is the one thing that no one can take from you,” she said.

But she has found that not everyone sees education the same way she does. She said she understands the true value of a free education and believes her students should feel fortunate for the opportunities they are given.

During her time as an educator, Buckhaults has found that handling the students and the classroom was not the difficult part, interacting with the parents was.

Lyon also believes that the main thing he was not prepared for when entering the classroom was the parents.

“Lack of parent involvement or the over abundance of parent involvement in some cases, so it just kind of depends,” Lyon said. “Seems like there’s not really a happy medium.”

The state of Oklahoma has started to make changes within the education system, and the teachers continue to stand together until what they believe is needed has be achieved.

Buckhaults said she wishes there was some more support from the positions above her within the state. She has found that often demands that come down the chain do not fit her classroom or her students.

“Spend at least a week or two in my classroom and get to know my kids,” she said. “What you’re trying to make me do may not work and its probably not going to. I’ll try it. I’m not against trying anything, but by this point I know what my kids need.”

Lyon also weighed in on the fact that some areas might benefit from less state involvement.

“We’ve had some support, but there are other arbitrary things that they come up with that seems kind of foolish and you know,” Lyon said. “I don’t know why they think that they need to be able to control how many days we’re in school instead of letting the district decide what’s best for them.”

Overall, educators across the state still see room for progress, but those in Alva have been satisfied with their support system and community.

“I really can’t say that I’ve faced tons of challenges,” Eckhart said. “Here in Alva we have great administration, we have a really great principal and I’ve always had really great leadership here.”