By LANEY COOK, Student Reporter

She was running late to her midterm exam. Then her work phone started ringing again, forcing her to decide whether to answer the phone and risk missing the exam – or make it to the exam but miss what could be an important call.

When she answered the phone, she heard: “We have been trying to reach you about your car’s extended warranty.” She immediately hung up and had just enough time to make it to her test.

That phone call was a dud, but the phone rings a lot with a real person – and an important issue – on the other end. That’s just another day in the life of Savanna Taylor.

Taylor, a full-time graduate student from Marshall majoring in social work and counseling, also works 40 or more hours each week at the Vocational Rehabilitation Department for the State of Oklahoma. Her workdays start at 7 a.m. and end between 5:30 and 6:30 p.m. Classes are thrown in the mix, including a night class every Wednesday.

She is not alone. Counselors and healthcare professionals across the nation report that mental health issues are becoming more prevalent, especially among college-age people.

WORK-SCHOOL BALANCE HARD TO JUGGLE

Working full-time and being a full-time student is exhausting, Taylor said, but her boss allows her to have a flexible schedule.

Taylor’s job as a social worker aligns closely with her studies in social work, which can make separating work from school challenging.

“It’s kind of like having to compartmentalize myself constantly between work and school,” Taylor said. “I can’t act the same in front of my clients as I can in front of my colleagues and peers, and there’s only so many hours in a day.”

Another Northwestern student, who remains anonymous for privacy reasons, is a full-time student majoring in business and has a full-time job as a certified nursing assistant. She said she struggles to keep up with her job and school work.

She was diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, depression and epilepsy before coming to college.

“I struggled coming into college, knowing I wouldn’t be able to drink or party as much with everyone,” she said. “With epilepsy, it’s really dangerous to drink, and before I knew I had it, I partied a lot, and it got kind of scary there for a little bit.”

Her seizures tend to increase during the school year because of the added stress of class and homework, she said. She manages her stress and illnesses by keeping herself busy, she said.

“I don’t have a healthy coping mechanism,” she said. “I honestly just try to avoid it. I try not to think too far into the stress, and when I hit my breaking point, I’ll go back to my mom’s house to try and get advice from her.”

She believes other people feel the same way but act as if they’re mentally OK, even though they’re struggling in reality. But she said she has “no reason to cover it up.”

WORKPLACES ADAPTING TO MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES

The number of Northwestern students and workers seeking counseling has recently spiked, said Taylor Wilson, the university’s director of counseling and career services. Wilson said she believes the increase, however, may be a result of greater dialogue about mental health issues that help reduce the stigmas surrounding treatment.

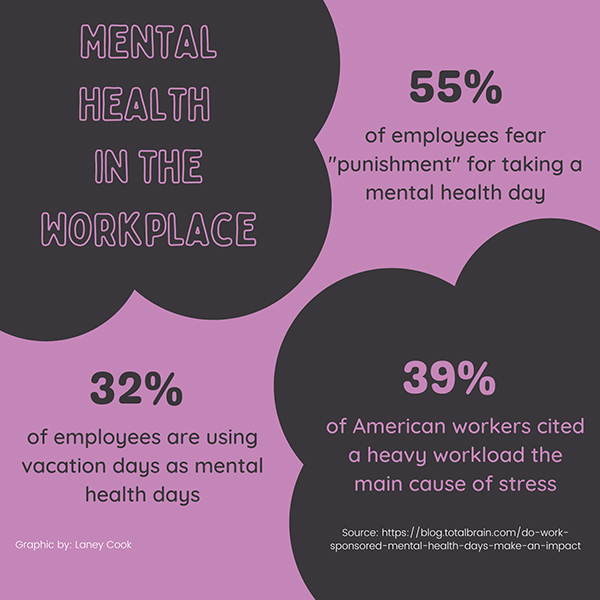

Companies across the nation have also reported that a greater number of employees are using mental health days to take off work rather than using sick leave, vacation time and holidays. Companies report that mental health days for employees have been helpful, and they help show employees that companies care about their well-being.

Employees who use mental health days usually don’t have to explain why they’re taking that time off.

Mental health issues can significantly impact employee productivity, according to Total Brain, a tech company that aims to help people improve mental wellness. Anxiety, depression, stress, and substance abuse can affect people’s ability to focus, remember information and connect with coworkers.

WORK-RELATED ISSUES, FINANCIAL CHALLENGES ADD STRESS

Work-related stress can worsen a person’s mental health issues, and so can financial worries.

People under financial stress are three times more likely to have a mental health issues, especially depression, anxiety and psychotic disorders.

Financial stress is common among college students, who have to pay costs such as tuition, rent, other school expenses and personal expenses.

In 2015, Health Day News reported that 70% of undergraduate students from 52 colleges and universities across the United States were stressed about their finances, researchers found in a study. Roughly 60% were concerned about being able to pay for school, and 50% were worried about being able to pay their monthly bills.

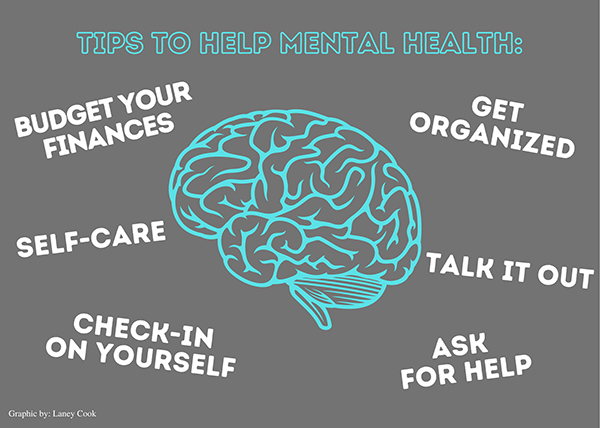

But in spite of the stress, students can take some steps to manage their financial concerns, Wilson said. Budgeting monthly income with monthly bills helps students see exactly where their money is going.

“I create a budget,” Wilson said. “I have a due date for when it’s due, and once I’ve paid it, I highlight it or cross it off. It helps keep me on track and lets me see where my money goes.”

Taylor, the graduate student, said she uses guidance from financial guru Dave Ramsey to create a monthly budget.

“The one month I really stuck with the plan, I saved a little over $700,” Taylor said.

Most mental health-related issues stem from childhood trauma, said Taylor Randolph, a psychology instructor on Northwestern’s Enid campus. The way parents treat and raise their children can unintentionally lead to mental health issues later in life. Many people don’t take this into consideration, Randolph said.

A study in the late 1990s, the Adverse Childhood Experiment Survey, connected stressed caused by obesity to childhood trauma, Randolph said. The study helped re-frame the way people look at how childhood experiences affect people in adulthood.

“Our childhood experiences affect our behavior and personality in adulthood, even if we were not aware of the existence of this connection,” according to Chrysalis Courses, a counselor training center. “In adulthood, we continue to strive to fulfill the desires we developed in childhood.”

People who have had more adverse childhood experiences tend to be more at risk for obesity, depression, anxiety, smoking, alcoholism and substance abuse, Randolph said.

“We’re really good, to a fault, when it comes to mental health about applying a label and trying to describe something,” Randolph said. “But we’re less good, many times, at looking at the ‘why’ and ‘where did this come from’ aspect of it.”