Green Beret veteran has message: Don’t take vets’ service for granted

By DR. ROBERT J. ARMSTRONG, Guest Columnist

“Would all of those who have served in the Armed Forces please stand?”

I stood as did many others in the audience who had come to hear the Memorial Day program by The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square that would begin its weekly broadcast in just a few minutes.

The program host continued.

“We want to thank you for your service, especially those of you who served in Vietnam,” he said.

Then the applause started and so did my tears.

To this day, the remembrance of that public recognition still brings tears to my eyes.

At that time, it was more than 30 years since I had served in the U.S. Army as an infantry officer in the Republic of Vietnam.

And never once, in all those 30-plus years, had anyone, other than close family members, offered a kind word of appreciation to me or any other Vietnam veteran that I knew of.

But, at least for that short moment in time, we were no longer the forgotten warriors.

At the end of World War I, World War II and even the Korean War, veterans had been welcomed home with parades, pats on the back and other such outpourings of appreciation from their fellow Americans.

But the typical Vietnam veteran was welcomed home with hard glares, shunning and even being spat on by his fellow countrymen.

Rudyard Kipling recognized this same treatment when he penned the poem “Tommy” in 1890, contrasting how the public treated British soldiers during peace and during war.

He could have been writing about U.S. Vietnam veterans. Part of the final stanza goes like this:

“For it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ ‘Chuck him out, the brute!’ But it’s ‘Saviour of ’is country’ when the guns begin to shoot.”

In some ways, I was more fortunate than most when I returned from Vietnam.

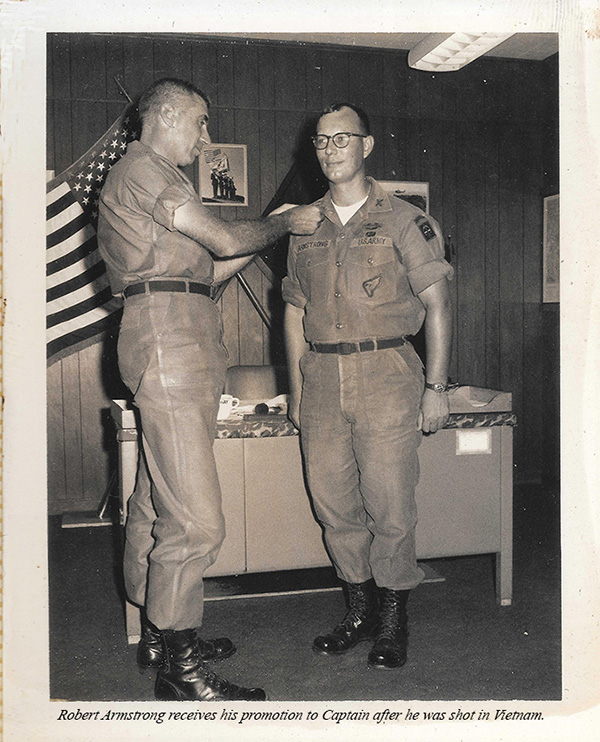

Because I had been shot in the jaw while in combat, I came home via the medical system, which kept me sheltered from the harsh words and other hurtful actions most other Vietnam vets faced.

I was able to ease back into society, being nurtured by my dad, himself a World War II veteran who had spent about two weeks in a north African German prisoner of war camp before escaping.

The love and understanding from my dad certainly helped ease the trauma of my ’Nam experience.

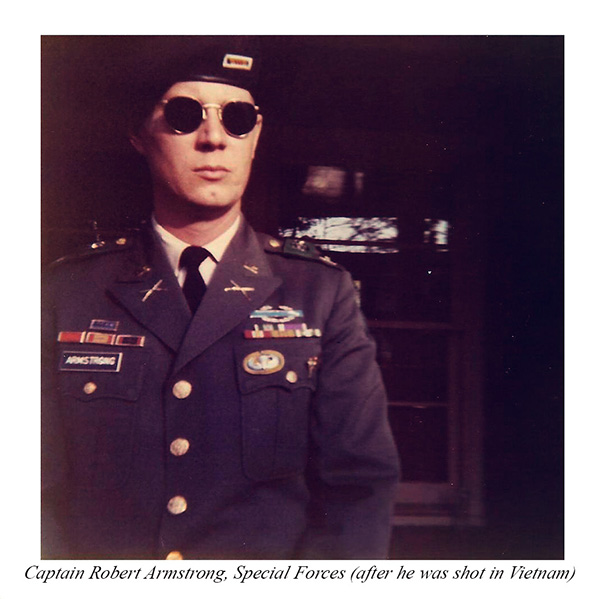

For the next four years, I continued to serve my country, first as a company commander of an airborne infantry rifle company in the 82nd Airborne Division and then two years as an A-team leader in 5th Special Forces Group (Green Berets).

It was a HALO team. (It has nothing to do with the video game of the same name.)

Actually, HALO stands for “high altitude low open.”

Even though we were capable of jumping out of airplanes from as high as 45,500 feet, the highest I ever jumped from was 20,000 feet.

What a rush.

Depending on the mission, we would open our parachutes anywhere from 4,500 feet to as low as 2,500 feet above the ground.

Then the Vietnam War wound down, and the Army began to cut back the number of personnel it needed on active duty.

And there I was, a civilian again.

So, I went back to school and eventually became a doctor of chiropractic.

Yep, I had gone from being a trained killer to being a trained healer. In other words, I got on with my life.

But to this day, a number of Vietnam vets still have not been able to move on. Many of them have settled down, raised families and got on with life, just as I did.

However, some didn’t. They wound up homeless and/or on government subsistence. They finally have a name for it: PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder).

Actually, most of us, in spite of our outward attitude of indifference, still — in our hearts and because of our love for our country — feel some sorrow at not having been welcomed home as warmly as other veterans.

But what we all have in common is something I was once told, and did not realize the truth of, until I experienced it for myself.

And that something is this: “For those who have fought for it, freedom has a taste the protected will never know.”

Remember, Vietnam veterans answered their country’s call to duty, even when it wasn’t popular. If you know a veteran, especially a Vietnam veteran, just let them know you are grateful for their service.

They may not show it, but rest assured, they will be grateful for your kindness.

Please, don’t let them continue to be the forgotten warriors.

Dr. Robert Armstrong is the husband of Northwestern News Adviser Dr. Kaylene Armstrong.