By JORDAN GREEN, Editor-in-Chief

The Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks were defining moments in the lives of college students.

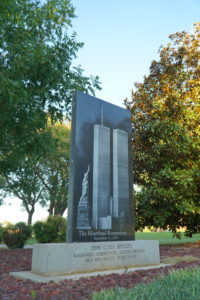

And thanks to Northwestern’s 2006 class officers, a monument honoring the people affected by those attacks remains a defining part of Northwestern’s Alva campus.

For several years, a tall, black slab blazoned with an engraving of the World Trade Center has stood in a green-space on the northwest corner of the university’s campus. Nestled beneath trees and surrounded by lush grass, the monument gives people the chance to understand more about one of America’s darkest days, the officers say.

“It’s a pivotal event in history,” said Dedrianne “Dee Dee” (Miller) Stevens, one of the class officers who helped raise funds for the monument. “You don’t forget where you were, what you were doing when it happened. And you know that, from that moment on, you won’t be the same.”

With the 20th anniversary of the attacks just two days away, Americans are sharing their stories from 9/11. Among them are college students whose lives would be forever marked by the events of that day.

THE HEARTLAND RESPONDS

Across the nation, Americans’ emotions ran high after the Sept. 11 attacks. Candlelight vigils and prayer ceremonies sprung up overnight, and attendance at church services increased for weeks after the attacks as the nation’s troops were whisked off to war in the Middle East.

Those emotions didn’t diminish quickly.

Even a few years later, Northwestern’s class officers still wanted to pay tribute to those who died – and those who rendered aid to others.

For several months, the officers sold hoodies at sporting events and hosted bake sales to help pay for the monument, which was installed on campus shortly after their graduation, university officials said.

It was an effort unlike any other, said Northwestern President Dr. Janet Cunningham.

“A lot of our senior classes don’t get that involved – but they did,” Cunningham said. “They kind of wanted something left to remember them by, too.

“That was a devastating event to the whole country, and I think everybody who was old enough to remember it, it impacted them greatly. We think that’s a good thing to remember.”

The officers concur.

“After 9/11, everyone was in a reflecting mood,” Stevens said. “We thought a monument might be good to commemorate the occasion.”

THEIR STORIES

The monument means something special to the class officers, they say. Like the monument, their stories of that day have lasted through the years.

Stevens remembers exactly what she was doing that day. She walked into her dormitory room around 9:30 that morning. Her suite-mate had the TV on.

Just as countless other Americans did, they watched a plane crash into the World Trade Center on live television. They saw the Twin Towers catch on fire. They witnessed people covered in blood and ash as they ran through the streets of New York City, crying out for their loved ones.

“As the events unfolded that morning, you had no idea how far-reaching it would be,” Stevens said. “You didn’t realize at that moment that life as you knew it would cease to exist.”

Jocelyn (Sweeden) Kaspar, who was the president of her graduating class at Northwestern, was a Shattuck High School senior when the attack happened. She sat in class and watched the scene unfold.

“It seemed to change everything in the moment,” Kaspar said. “You knew it was a big deal.”

PRESERVING HISTORY

The monument is a way “to remember the sacrifice people gave, remember all the people that came and helped, all of the families that are still mourning their loss,” Kaspar said.

It’s also a tool to help current and future Rangers learn about the attack. Most current college students are too young to remember it, yet their lives are still different because of it, Stevens said.

“I think it’s meaningful just to have something on display to see, just for people to look at, reflect and remember,” Kaspar said. “Now, it seems so old. People who are younger … they probably don’t remember many details of 9/11.”

That monument, like the day it commemorates, won’t be forgotten soon, Stevens said.

“A lot of kids that are younger than 20 years old, they don’t know a life before 9/11,” Stevens said. “Your lives were forever changed from that moment on.”