By JORDAN GREEN, Editor-in-Chief & DAVID THORNTON, Photographer

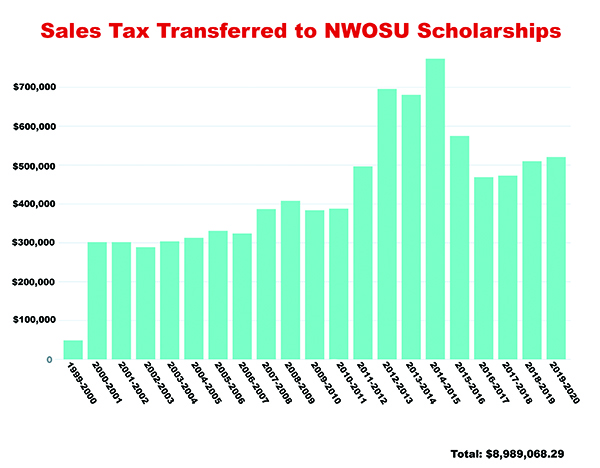

9 Million. In two decades, that’s about how much money the Alva Incentive Tax has raised to fund scholarships for NWOSU students.

In 20 years, a 1% sales tax in Alva has collected almost $9 million in scholarships for Northwestern students.

That tax is called the Alva Incentive Tax. And you might be one of the countless Northwestern students who has received money from it.

Amid fear of losing the university, Alva voters in 1999 passed a sales tax aiming to develop the economy of this rural northwest Oklahoma town. Half of the funds collected from the tax would be used to build a new public recreation center in Alva, and the other half would be used to fund scholarships for new Northwestern students.

“It’s worked very well,” said Northwestern President Janet Cunningham, who advocated for the tax.

In the years since it was passed, hundreds of students each year have received scholarships funded by tax collections, encouraging students to attend the regional university and spurring economic growth in a rural area that otherwise relies on cyclical, boom-and-bust industries.

“The university being here is a huge driver for the city,” Cunningham said. “Not only the students – they do a lot – but the faculty and the staff, and even the more non-dollar benefits of having an educated component to your community that fill your public schools with their kids and fill your churches, community groups and so on.”

WHAT IS THE TAX?

The Alva Incentive Tax is a 1% sales tax that began in 1999. Sales taxes are applied to almost anything a person purchases within the city limits, with some exceptions.

The City of Alva collects money from this tax when people purchase goods at local stores, food at restaurants, fuel at gas stations and just about any other item sold within the city limits.

Alva’s overall sales tax rate is 9.25%, according to the Oklahoma Tax Commission. That total is comprised of the city’s 4.25% sales tax – which includes the 1% for scholarships and economic development – as well as the county’s 0.5% tax and the state’s 4.5% rate.

According to data obtained from the City of Alva, the university received $8,989,068.29 from the tax from June 1999 – when the tax went into effect – to the end of fiscal year 2019-2020.

Revenue from the tax is deposited into the city’s Economic Development Fund each month, City Manager Angelica Brady said. That money is invested in certificates of deposit, which earn interest. The interest is also available for scholarships, and the city doesn’t charge the university a fee to manage the fund.

“[CDs] are pretty stable, and we do our CDs through our local banks,” Brady said. “They usually work with us quite well to do that. It makes it more accessible.”

To get money out of the fund, the Northwestern Foundation and Alumni Association bills the City of Alva twice each year for the amount of money the university paid out in scholarships during the previous semester. In January and May of each year, foundation officials and university administrators make a presentation before the Alva City Council to discuss how many students received scholarships and what their economic impact on Alva is.

The Council approves the bill, and the amount of money requested – which fluctuates depending on the number of scholarships awarded – is paid to the foundation office. The foundation office then transfers that money to the university, where it is doled out to new Rangers.

“It’s pretty straightforward,” City Manager Angelica Brady said.

WHY WAS IT PASSED?

In the late 1990s, a series of legislative measures at the State Capitol led some community stakeholders to worry that Northwestern might leave Alva.

“In ’96, ’96-’97, the Legislature gave us the higher education function in Woodward and in Enid,” Cunningham said. “Of course, there was already a higher ed center in Enid and a building that had already been built, very nice, so on. I think there was some fear that those were both larger communities, and you know how things kind of get in people’s minds, and sometimes you use it.”

Champions of the tax initiative had two main goals: create a recreation center for the city, called the Alva Recreation Complex, and maintain Northwestern’s standing as one of the most influential pieces of Alva’s economic puzzle.

Cunningham said she encouraged the university’s then-president, Dr. Joe Struckle, to market the measure as a way to “maintain the university’s presence in Alva.”

“We really tried hard as a university to sell the model that we have one university, we just happen to have several sites,” she said. “And really, what’s good for Enid is good for Alva, is good for Woodward. But people can’t always see that.

We could be too parochial – you look at your own little ‘piece’ of the world, and you look at any encroachment on that as hurting you, rather than looking at the region of the state.”

WHAT DOES IT PAY FOR?

Scholarships from the tax may only be given to first-time Northwestern students, whether they’re incoming freshmen or transfer students. Tax revenue helps pay for scholarships during school visitation days, such as Ranger Preview, where students receive a $600 scholarship if they enroll at Northwestern. This is used as an incentive to bring students to Northwestern.

Money from the tax also helps fund scholarships for students in athletics, choir, the Student Government Association and other groups at Northwestern.

The university’s Fine Arts department is just one example of an area where students can receive scholarships from the tax. Dr. Karsten Longhurst, Northwestern’s director of choral music, said singers in his choirs receive participation scholarships. For the first year students are at Northwestern, their participation scholarships are funded by the Alva Incentive Tax.

Longhurst has three choir classes. Each is on a different “level,” meaning students qualify for differing amounts of money depending on the classes they’re in. Those classes are the University Singers, Chorale and Concert Choir.

Concert Choir students can receive $500 per year, Chorale students can receive $1,000 and Singers can receive $2,000.

Every choir student who is in the university’s four-year music program is promised one international tour along with “mini-tours” around Oklahoma. Support from the Alva Incentive Tax makes these trips possible, Longhurst said.

“The tax is one of the most amazing things the Alva community has agreed to do,” Longhurst said. “In a town of 5,000 people, the university provides entertainment, fitness and economic impact.”

As part of the economic development portion of the tax, the city used money to build the city’s recreation center. As a result, Northwestern was able to start a women’s soccer team and a women’s softball team. Before it was built, those teams would have had nowhere to play. But once the facility was built, they did. They still play there today.

Pecha said the tax helps set Northwestern apart from other universities.

“It has allowed us to recruit students that we might not have ever had a chance to ever recruit,” Pecha said. “It gives us an extra resource to be competitive, especially for a university in a rural setting, to help sell the assets that we have here.”

TAX’S IMPACT ON NORTHWESTERN AND ALVA

Since it was passed, the tax has collected an annual average of about $430,000 each year for Northwestern students, adding up to almost $9 million.

Yet the impact of that money is significantly greater, said Skeeter Bird, president of the Northwestern Foundation and Alumni Association.

The tax provides a relatively consistent stream of revenue for students – barring any unforeseen economic downfalls, like when businesses closed because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The impact of the tax – even though it has brought in $9 million – is equal to that of a much larger endowment. The only other way the City of Alva could fund the same amount of scholarships it currently does would be by creating a $15 million endowment to the university, Bird said.

“If you think about how many students make a decision to come to Alva because of that extra $500 to $1,000 that they get from the Alva Incentive, that impacts our community,” Bird said.

So, what is the tax’s economic impact?

Using figures provided by the U.S. Department of Education, Bird has calculated the amount of money the average Northwestern student likely spends in Alva each year.

In the fall semester, when the university had 1,166 students on the Alva campus, each student likely spent around $3,359 in Alva, according to Bird’s calculations. In total, students spend more than $3.9 million annually.

In the fall semester, 287 students received scholarships from the Alva Incentive Tax. They likely spent about $964,000.

“Every student that makes a decision to come here, what they spend at downtown, Walmart, or anything actually comes back,” he said. “If you go full circle and you think about the tax dollars, they spend money to create their own scholarships before they leave at the end of the summer.”

NOT ALL DATA TRACKED

How many students have gotten Alva Incentive Tax scholarships?

That number can’t be determined.

Northwestern hasn’t consistently tracked the total number of students who have received scholarships from the fund, Pecha said.

Each semester, university officials prepare a detailed list of students who receive scholarships and the number of scholarships they receive. However, some students receive a scholarship for both semesters of their first year here, and some receive it for only one semester if they leave the university.

Those factors make the total numbers hard to decipher, Pecha said.

“Nobody has tracked that data from the beginning,” Pecha said. “I don’t know of a comprehensive way to try to track that data. I kind of wish whoever had started this would have tasked that to somebody so we can keep records. Now that we look back on it after 20 years, it would be so cool to find out how many lives it touched.”

Pecha said the university could track such data in the future.

“It’s easy to pull the data when you’re working with it in that current period of time,” he said. “If you try to go back 15 years and pull something, it’s more challenging.”

PLANNING AHEAD

Sales tax collections vary, and when economic disaster strikes, sales tax collections decline.

That’s why officials keep a year’s supply of money from the fund in reserve. A certain amount of money remains in the account maintained by the city in the event that Alva’s sales tax base ever collapsed.

Students come to Northwestern at events like Ranger Preview months before they enroll at Northwestern, and they’re promised scholarship money when they visit. But in the time between their campus visit and their first semester, things could change. By keeping money set aside in case of an economic emergency, Northwestern officials could continue to pay scholarships promised to students during events like Ranger Preview. Then, they could readjust their plans for the future, Bird said.

The amount of tax revenue has fluctuated through the years. From fiscal year 2000-2001 – the first full year of sales tax collections – to the 2010-2011 fiscal year, the tax collected about $388,000 per year.

It reached a high of $774,955.62 in 2014-2015, during the peak of an oil boom across the Midwest. But as oil prices dropped, so did sales tax collections. In 2019-2020, it collected $521,749.11.

ONE-OF-A-KIND PROGRAM

Only one other regional university has had a sales tax that funds scholarships: Northwestern’s rival, Southwestern Oklahoma State University.

In 2000, Weatherford residents passed a 1% sales tax renewal that helped fund a scholarship endowment at the university. Scholarships from that fund could only be given to students who have completed an associate’s degree and are pursuing their bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees, said Sheridan McCaffree, executive director of the Regional University System of Oklahoma.

That’s unlike Northwestern’s program, which directly funds scholarships for first-time students.

Other cities in Oklahoma have passed sales tax increases to build new facilities at universities, but those taxes have a sunset date, meaning they eventually come to an end.

“None of our other universities have a specific sales tax for a scholarship program like Northwestern does,” McCaffree said.

McCaffree said the Alva Incentive Tax scholarship program could be a role model for other universities.

“Northwestern was the first one to do it,” she said. “I remember it was pretty groundbreaking when Alva did it. You know, I just assumed everybody fell in line after that.”

LOOKING TOWARD THE FUTURE

While sales tax collections dived during the pandemic, Brady, the city manager, said the city’s economy is improving. Sales tax collections are rising once again.

That’s a promising sign for scholarships at Northwestern, she said.

“For our city, we’ve done quite well,” Brady said. “Other cities, in less rural areas, they have struggled with losing sales tax. But for us, what we feel like is people are staying here and shopping here. We’re gaining some [revenue] we may have lost.

“I’m very happy with where we’re at. It’s a great thing for our community.”